6 Minute YouTube video embedded at the bottom of the page

FORT WAYNE, Ind. (WANE) — Last year, Jeff knew a key piece of evidence would clear him of the two misdemeanor charges he faced.

The problem?

FORT WAYNE, Ind. (WANE) — Last year, Jeff Williams knew a key piece of evidence would clear him of the two misdemeanor charges he faced.

The problem?

He couldn’t have a copy of the body-cam video, which showed his brother telling a New Haven Police officer there was no physical contact between them.

“I was not going to feel even potentially safe unless I could get a copy of it,” Williams told 15 Finds Out, “because things do disappear. It may be rare, but it does happen. You want that on a USB drive in your pocket.”

Eight months later, both the class A misdemeanor charge of domestic battery and the class B misdemeanor charge of disorderly conduct would be dismissed unconditionally.

“I was surprised to find out that I [was] not allowed to have any of the evidence,” said Williams. “I [could] go view it, but I [couldn’t] have it.”

Williams believes his case would been faster and less expensive if it had not been in Allen County, where the Prosecutor’s Office has created a unique policy to limit a defendant’s access to evidence, which seems to be widely accepted by the local legal community, but questionable to some of those outside it.

To protect victims

Allen County Prosecutor Mike McAlexander told WANE 15 his office has adopted an “open file concept” for sharing evidence with defense lawyers.

“If it’s in our possession, we let the defense know about it,” he said. “We don’t do trial by ambush. We actually go farther than what the rules ask for.”

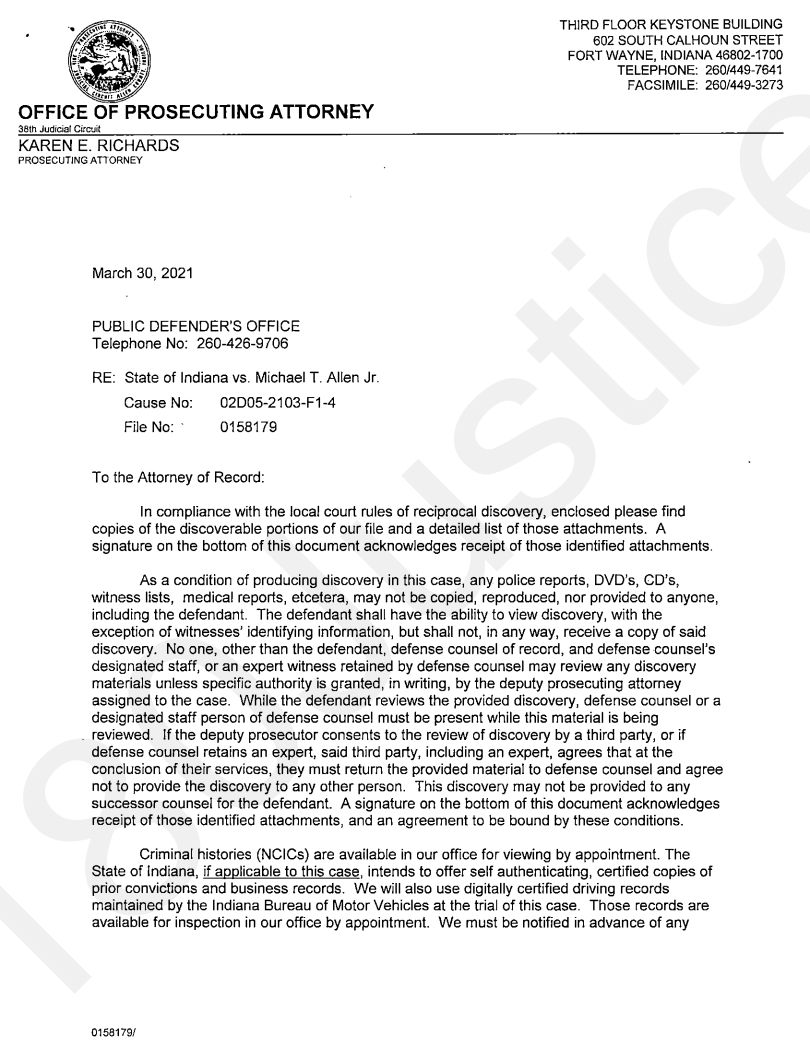

According to Allen County’s local rules of the criminal court, the State must share evidence in any manner “mutually agreeable” to the Prosecutor’s Office and the defense counsel.

For the last decade or so, “mutually agreeable” has meant defendants can view the evidence against them only under the supervision of their defense lawyer.

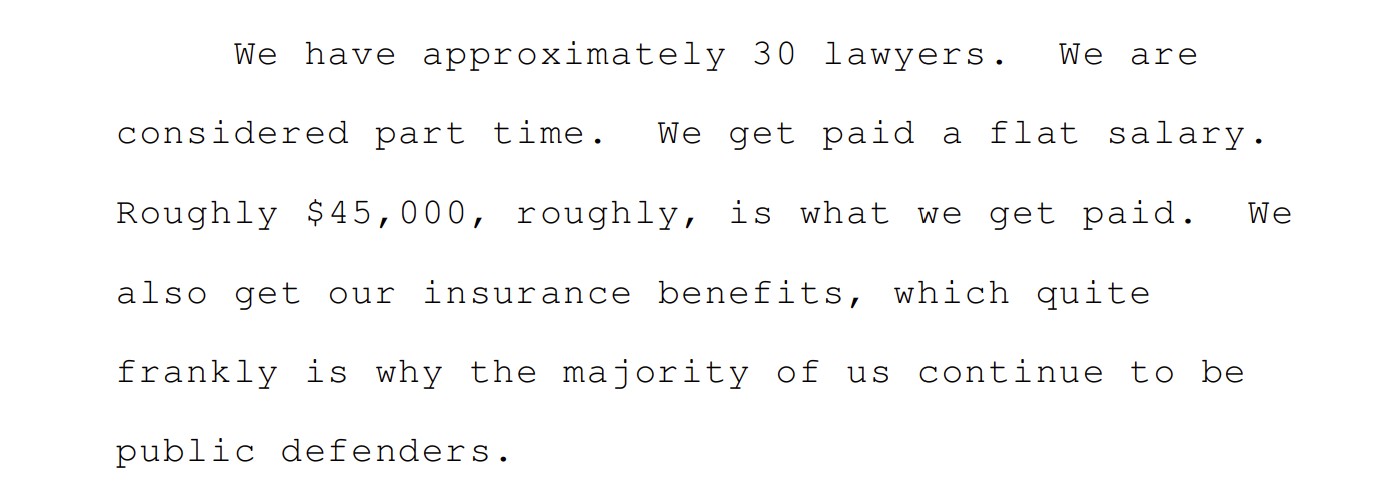

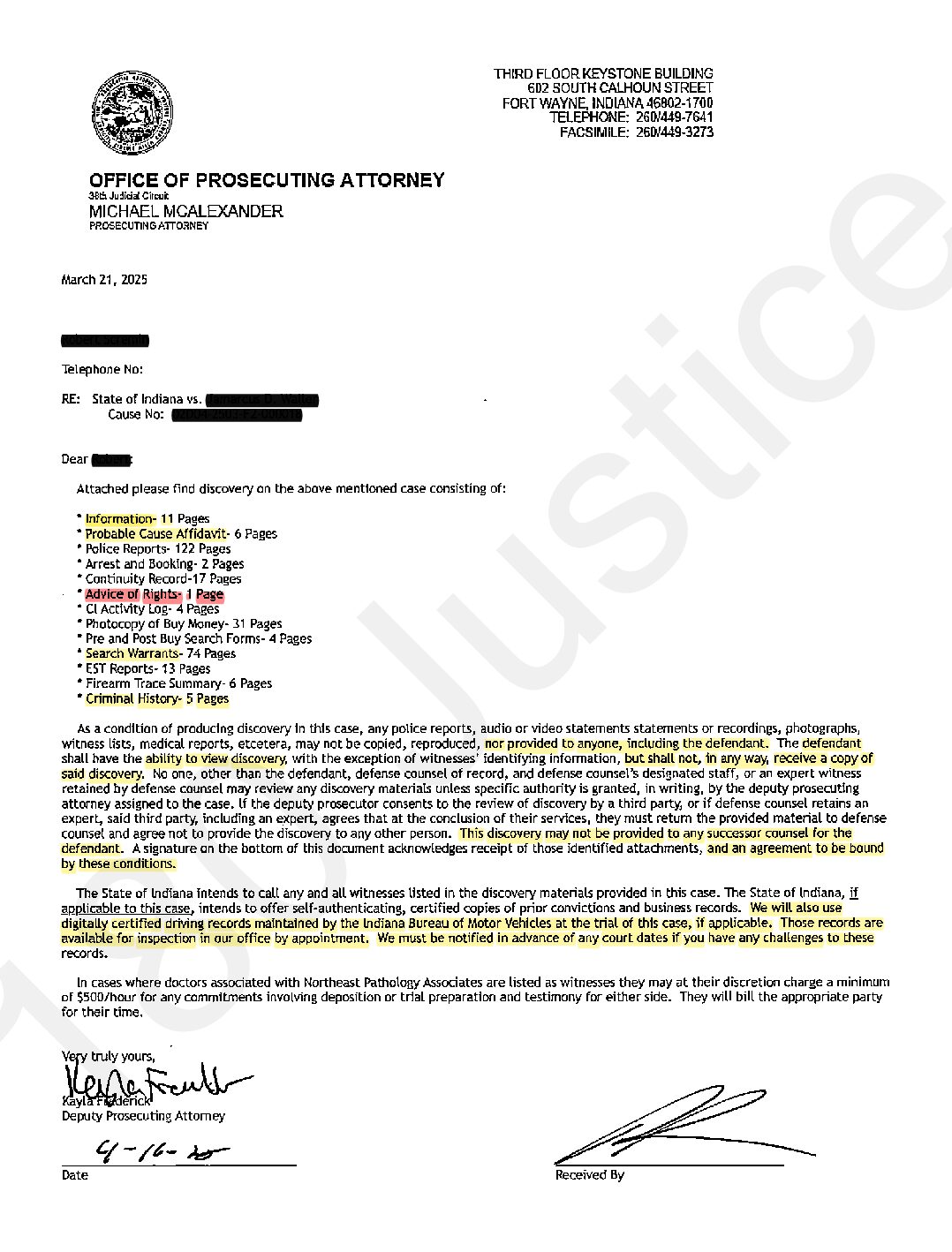

“The defendant shall have the ability to view discovery, with the exception of witnesses’ identifying information, but shall not, in any way, receive a copy of said discovery,” is the common language from the Allen County Prosecutors Office (ACPO).

McAlexander said the arrangement is mutually agreeable, since defense lawyers get “open file” access and prosecutors keep sensitive material from becoming public, which can retraumatize crime victims and possibly lead to mistrials, forcing victims to endure an additional proceeding.

“We recently had a case where autopsy photos were leaked and were put out on the internet,” he noted, adding cases involving children or sex crimes especially need to focus on the privacy and confidentiality of the victims.

Due to the volume of cases prosecuted by his office, McAlexander did not think obtaining protective orders for individual pieces of evidence would be workable.

“Obviously to the defendant, they’re only worried about one case: theirs. Everybody else in the system is juggling a lot of different things.”

‘You’ll get it anyway’

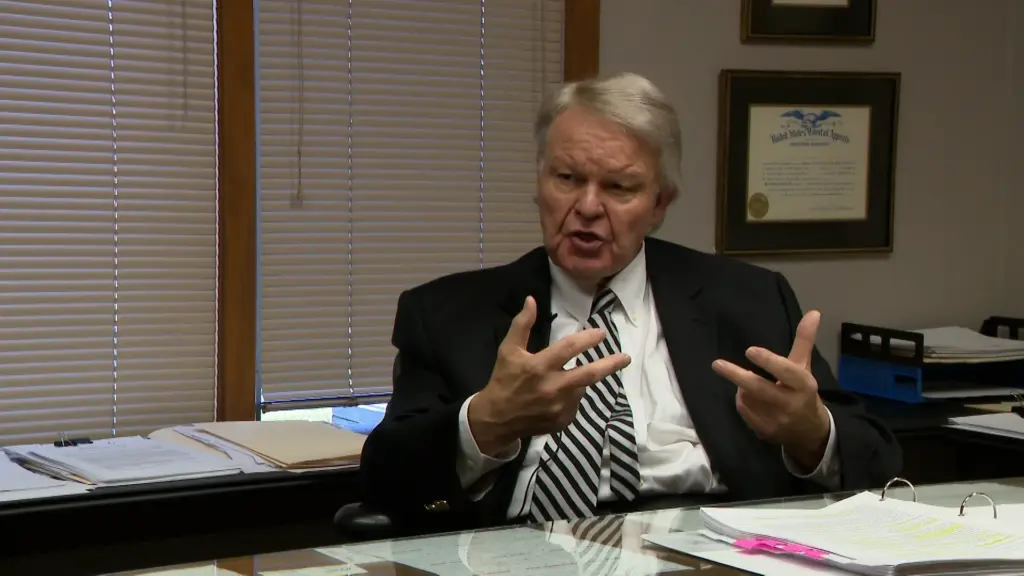

“You don’t have to sign these [agreement] letters,” defense lawyer Richard Thonert told 15 Finds Out. “If you do sign them, you get immediate discovery. If you don’t sign them, it may take a little while, but you’ll get it anyway.”

Thonert has been a defense lawyer since 1974, arguing cases across Indiana from speeding tickets to murder.

Only in Elkhart County has he seen a policy similar to the one in Allen.

As a practical matter, he doesn’t find the ACPO policy a problem. Thonert contends most defendants not in pre-trial custody don’t object either, and simply treat a legal consultation like a visit to the doctor’s office; few patients want to go home afterwards and pore over their medical records.

However, in 2019, Juventino Ramirez, who was accused of child molesting, told Thonert not to sign the letter.

As a result, the Prosecutor cited local court rules and withheld a videotaped victim statement, forcing Thonert and Ramirez to watch it at the Prosecutor’s office by appointment.

Thonert objected to the restriction, which he thought could limit his ability to craft a defense, since he might work on the case “at 2 or 3 in the morning as opposed to 2 or 3 in the afternoon.”

The Ramirez case led the Indiana Supreme Court to blow up Allen County’s previous local discovery rule, saying it was “without force and effect” because it attached conditions on Indiana’s discovery rules, “which are meant to allow liberal discovery.”

The ruling made no mention of the policy of the prosecutor’s office or if a defendant can be restricted to view evidence only during office hours.

But after the Ramirez ruling, Elkhart County revised its blanket policy to be more content-specific.

How it’s done elsewhere

“This is such a non-issue,” said Christopher Wellborn, a 34-year South Carolina defense lawyer and the president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

“Maybe Fort Wayne, Indiana is different and everybody’s on Facebook and there’s all kinds of jury tampering involved,” he wondered sarcastically. “I’m not saying it hasn’t happened, but I haven’t personally seen it.”

Wellborn said a prosecutor’s policy should not get to determine his relationship with his client. If a client wants his case file, including all the evidence, he would be obligated to give it to him, even if the client wanted to use the file to seek a second opinion.

Wellborn recalled a recent case where his client was accused by a witness the prosecutor did not want to identify, because, the prosecutor said, some lawyer in the past had put up a billboard calling the witness a snitch.

Wellborn had three thoughts:

- How had he never heard that story if it really happened?

- How fast would he lose his license if he did that?

- Why not simply get a protective order that says he cannot name the witness on a billboard?

That was the only time he had experienced anything close to the ACPO policy.

However, he does not give evidence to every client, if sharing is at cross purposes to the client’s case.

“If he’s going to share it with 20 alcoholics down at the local bar and it’s going to get spread all over the place then no, I’m not going to do it,” he said.

He would also not give the trove of evidence to a client in pre-trial custody, for fear someone on the cell block would use the details in the discovery to fabricate an accurate, but false, jailhouse confession.

“But in a normal case, where a client is out on bond, where I’m not worried about something like that, and there’s no court order precluding it, if a client wants their file, they get their file.”

Across the state of Texas, it’s a different story.

Like the ACPO policy, defendants in Texas can inspect the discovery, but cannot retain copies.

As part of a 2013 overhaul of discovery practices, Texas law required prosecutors to disclose evidence fully and automatically to eliminate wrongful convictions.

Steve Brand, a criminal defense attorney in Austin, said while he finds it frustrating, there has been little pushback by Texas defense lawyers to the personal possession ban for defendants.

“We are happy to have the discovery to begin with,” he emailed WANE 15, “and nobody really wants them to start chipping away the other way.”

He thought defendants should be entitled to everything “with identifiers redacted” and that Texas lawmakers added the rule to “make them feel good about themselves.”

Local pushback limited

“I don’t know that I’ve ever felt like anyone was troubled by this policy,” said Prosecutor McAlexander.

Defendants who might be “burdened” with trips to their lawyer’s office have already had some measure of due process.

“We have submitted a probable cause affidavit. A court has looked at that information. They’ve made a decision about whether this person should be detained. And that ultimately falls not on us, but on the the court system.”

He occasionally receives “philosophical” pushback from private attorneys over who owns the discovery, but almost never from public defenders.

“We’ve made it work,” said Allen County Public Defender William Lebrato, who said the policy likely adds costs and labor to his office, which has to print and redact files and be available to watch defendants as they examine their evidence.

“It’s been in place so long, we don’t think about it,” he added.

Williams, who is on a fixed income, was frustrated by his public defender, who did not seek the 911 call in his case, which Williams believed could have helped prove his innocence.

Instead, a friend agreed to cover the cost of a private attorney, while Williams used public records requests to obtain some, but not all, of the evidence he was not supposed to see.

The 911 call cost him $25.

The motions, witness list, and probable cause affidavit?

No charge.

“As long as you don’t want a printed certified copy, you can just get that free,” he said, although the Fort Wayne Police Department website tells defendants in a current criminal case to contact their attorney “for access to the relevant police reports and dash or body camera footage through the normal discovery process.”

The city said this tip was posted to show defendants they would have greater access to evidence through the discovery process than what would be available through a public records request.

Using only public records requests, Williams was never able to get a copy of the body-cam video, which he finally saw at the public defender’s office, by appointment.

His private attorney was able to obtain a copy for him to keep.

“So on one hand, the system did work,” he concluded. “My charges were dismissed unconditionally.

“But it took eight months and it cost thousands and thousands of dollars that I don’t have.

“I don’t know how I’m going to pay it back.”

He has started a YouTube page to document his plight.

This story was updated to clarify how Williams obtained the body-cam video.

Here is a link to the Wane.com story

https://www.wane.com/investigations/justice-by-appointment-why-allen-county-limits-access-to-your-evidence/